On Election Day, many voters know about candidates and perhaps key issues. Probably far fewer voters, though, recognize the election officials who work 13 hours in a single day to ensure every eligible voter can cast a vote.

The city of Philadelphia has more than 800 polling places, a number that fluctuates and has not yet been confirmed for this election, according to the Office of the Philadelphia City Commissioner. That is more than 800 sites that must be staffed with between five and seven poll workers throughout the entire day.

Three of these poll workers — the judge of elections, majority inspector, and minority inspector — are elected to their positions, while a clerk and machine operators are appointed. At some polling places there are two machine operators as well as a bilingual interpreter.

Regardless of how they got involved, election officials have to prepare for their roles on Election Day.

Approximately 30 people gathered in the cafeteria of Mariana Bracetti Academy at 9 a.m. on Saturday, Sept. 28 for an election seminar hosted by the city commissioners. Poll workers are paid an additional $30 for attending the seminar, during which instructors run through Election Day protocol.

Attendees listened to a presentation by Shanna Fields (above), a representative of the Office of the City Commissioners. Most of the attendees were veteran poll workers, so the presentation went quickly and without any questions.

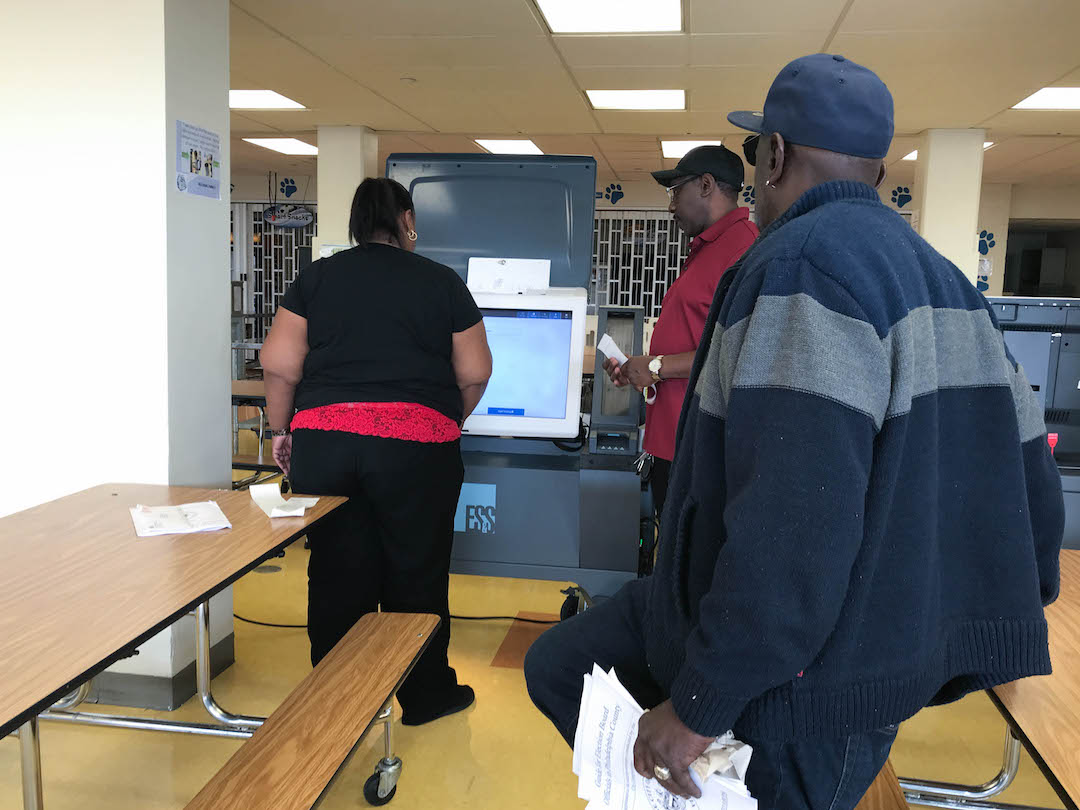

Carmelo Seminara (below), a representative from Democratic City Commissioner Lisa Deeley’s office, followed Field’s presentation with a tutorial on the new ES&S ExpressVote XL voting machines.

The new machinery is a subject for controversy in the city, and some poll workers, like Judge of Elections Rachel Murphy, had concerns regarding the machines.

“I’m extremely, extremely, extremely concerned about the voting machines,” said Murphy. “From many perspectives, I’m concerned about it.”

In August, The Hill reported on Philadelphia’s new voting machines because ES&S did not disclose its use of lobbying when the contract for new voting machines was signed. This disclosure, according to The Hill, would have disqualified the company from consideration.

“As a citizen who votes, I’m concerned because it’s been public that the whole process was really corrupt in choosing the voting machines,” said Murphy. “And Philly chose the most expensive, the least secure voting machines.”

Murphy is not the only person worried about the new voting machines. Protect Our Vote Philly is a coalition which, according to its mission statement, is working to stop the implementation of the Express XL voting machines.

Protect Our Vote Philly is supported by more than eight other partners including Indivisible Philadelphia and March on Harrisburg.

The Office of the City Commissioner will host demonstrations for voters as well as regularly scheduled training seminars for poll workers up until the election on Nov. 5. Seminara, who will serve as a voting machine technician on Election Day, said the machines are not connected to the internet and information will be sufficiently encrypted to prevent hacking. He estimated that Philadelphia had not purchased new voting machines since 2001.

“I think they’re very user-friendly,” said Seminara. “I don’t see any concerns other than older folks not wanting to learn new technology, which is understandable.”

Because working the polls requires a 13-hour day during the typical workweek, most poll workers are older adults who can use vacation days or retirees without set schedules. Ryan Godfrey, a 48-year-old minority inspector in West Philadelphia, has worked the polls for six years and has noticed most of his colleagues are significantly older than him.

“It’s kind of a long, hard, thankless job,” said Godfrey. “I find satisfaction in doing it because it’s giving back to the community in some way, but other than that … It may not be the most exciting job. There are other jobs that you can do like committee members and ward leaders that are more politically-engaging.”

Working in a polling place can be challenging because election officials have to ensure voters are being helped in a timely manner and have all their questions answered. Most of the time, voters are neighborly and satisfied, said Godfrey. But tensions can flare up if there is too much electioneering outside the polling place or if voters do not understand why they are asked for identification.

In Philadelphia, poll workers should only ask for identification if it is the voter’s first time voting in that division, said Fields during her presentation.

All poll workers in the city are paid for working on Election Day. Judges of elections are paid $120 for the day and other positions are paid $115, except for bilingual interpreters who are paid $95. Being paid, however, usually is not the main motivation of many poll workers.

“Well honestly, I just feel like they’re pretty strapped to make sure that every division has enough people there to work the polls,” said Murphy. “So I kind of feel like it’s a civic duty.”

More than 8,000 Philadelphians, a number estimated by the Office of the City Commissioner, will give back to their communities and help their neighbors vote on Nov. 5.

The Office of the City Commissioners is working to get more young people, like Murphy, 23, involved in working the polls on Election Day. In fact, ahead of the 2019 primary elections, representatives from the office traveled to three high schools in the area to train students, according to Seminara and Fields.

“We’re trying to get new blood into the actual voting process,” said Seminara. “It’s been tough, but I think we’re making a little bit of headway. We go there to recruit some kids because if you’re 17, you’re allowed to work on the polls. You just can’t vote [yet].”

Please email any questions or concerns about this story to: [email protected].

Be the first to comment