It’s 11:45 a.m. on a Friday in the Nicetown area of Philadelphia. Children and teenagers litter Germantown Avenue on an unusually cool April afternoon as they window shop and gather with friends on street corners.

On the surface, the sight seems like a pleasant one. One of youthful enthusiasm and innocence in an area riddled with crime and drug-use. When you look deeper at the situation, however, there’s one question that needs to be asked.

Why aren’t these kids in school?

Leon Mills, 15, stands on the corner of West Pike and Bouvier streets as he waits to meet with friends. Youthful in stature with a face that exudes experience well beyond his years, Mills explains that he’s currently enrolled at Olney High School, but says that he was able to leave school early today.

As Mills continues, he acknowledges that while he’s still currently a student, the majority of the younger people lining the streets are most likely former students.

“Dropping out is pretty common around here,” Mills, of Charles Street in Nicetown, said. “Whether it’s because a kid doesn’t have any parents, or because they start selling drugs, or even something like not liking their teachers, a lot of kids just stop coming.”

A former student of Elizabeth D. Gillespie Middle School, Mills remembers the daily life at the middle school that now faces potential closure at the end of the school year due to poor academic performance and declining enrollment as being one with a less than supportive atmosphere.

“The teachers talk to you like you was grown,” Mills says. “They’ll call you dumb, they’ll curse at you, they just act like they don’t really care… I think that teachers need to be held more accountable [for the performance of students].”

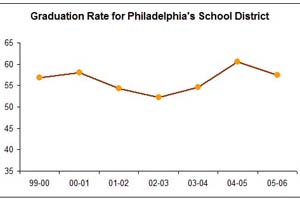

Accountability is a word that has been reverberating through the city as education has come to be a focal point of the Nutter administration due to a dropout rate that has consistently hovered around 50 percent in the city.

One idea that has been discussed as a means to remedy the situation is a merit-pay system for teachers. The idea behind the merit-pay system is that providing incentives to teachers would make it more likely for experienced teachers to work in a school that they would not have chose otherwise due to salary increases that come with fulfilling incentive requirements such as teaching science, speaking a second language or teaching in a hard-to-staff school.

“We’re really taking steps in trying to acquire the best teaching talent,” Philadelphia School District Human Resources Chief Estelle Matthews said. “We’re actively pursuing candidates, we’ve moved up our hiring time line, and we’re trying to be much more rigid in the candidates we consider.”

Traditionally, schools in a low-income area with a high-crime rate, such as Gillespie Middle School, have a lopsided portion of inexperienced teachers. The merit-pay system may enable these schools to alter this trend, however, by being able to offer qualified candidates more money for teaching in the hard-to-staff school.

The merit-pay system is a proposal that may be gaining traction in the city and across the country despite a history of staunch opposition from teachers.

District Superintendent Arlene Ackerman has put forward the idea of incentive pay for teachers in her five-year, $50 million plan “Imagine 2014”, which calls for financial and nonfinancial incentives for teachers.President Barack Obama has also publicly endorsed the idea of incentive pay for teachers. Saying in his first education-policy speech last month that “too many supporters of my party have resisted the idea of rewarding excellence in teaching with extra pay, even though we know it can make a difference in the classroom.” The prospect of a merit-pay system for teachers is not a new one in Philadelphia.

In 2000, the teachers’ contract awarded bonuses for teachers who worked in hard-to-staff schools. Also, in 2006 the district was awarded a $20.5 million grant to develop a teacher-incentive program. Both met with opposition from the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.

The district’s improved financial situation coupled with support from administrators may improve the district’s likelihood of reforming the way teachers are paid. Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, remains hesitant on the effectiveness of the program.

“We’re certainly willing to review all of the information that’s given to us,” Jordan said. “But I don’t think that offering the possibility more money to teachers will help improve performance. I just don’t think that’s true.”

Despite the support from high-ranking administrators, questions about the effectiveness of the merit-pay system remain because of a lack of evidence whether the system actually boosts student scores.

Matthew Springer, director of the National Center on Performance Incentives at Vanderbilt University said that it’s still too early to tell whether incentive-based programs would be an effective alternative.

“Performance incentives are an idea that is really gaining momentum in the education field,” Springer said. “But it’s still too early to tell whether or not it’s an effective reform.”

Whether the merit-pay system comes to fruition remains to be seen as the city and the teachers union negotiate a new deal that is set to take effect this September.

Regardless of the outcome of the merit-pay negotiations, the city still faces the task of finding the answers to some of educations most difficult questions, and some of its most important decisions on education in the city’s history.

Armed with approximately $3.1 billion in its treasure chest thanks to federal stimulus money and a boost in aid from Harrisburg, the city has the resources to make significant steps in improving the education system in Philadelphia. This is a change from recent memory for a district that has been financially strapped with deficits each of the past three years.

The stakes have never been higher for educators and administrators that have allowed approximately half of the students in the city to slip through the cracks. The chance that’s been given is a one-time offer, and it’s up to everyone involved to make the right changes to help students achieve. If they fail to make those changes, it won’t be too difficult to notice. Simply take a drive down Germantown Avenue in the middle of the afternoon on a weekday.

Be the first to comment