Amanda Bowman always imagined herself as a mother. When the time came for her to have children, she was presented with two surprises. The first: she would have to raise them as a single parent. The second: she was having twins.

Despite the challenges that faced her, she knew she was going to send them to preschool.

“I’m big on early ed,” she said. “I feel like its a foundation. It prepares them for a larger setting.”

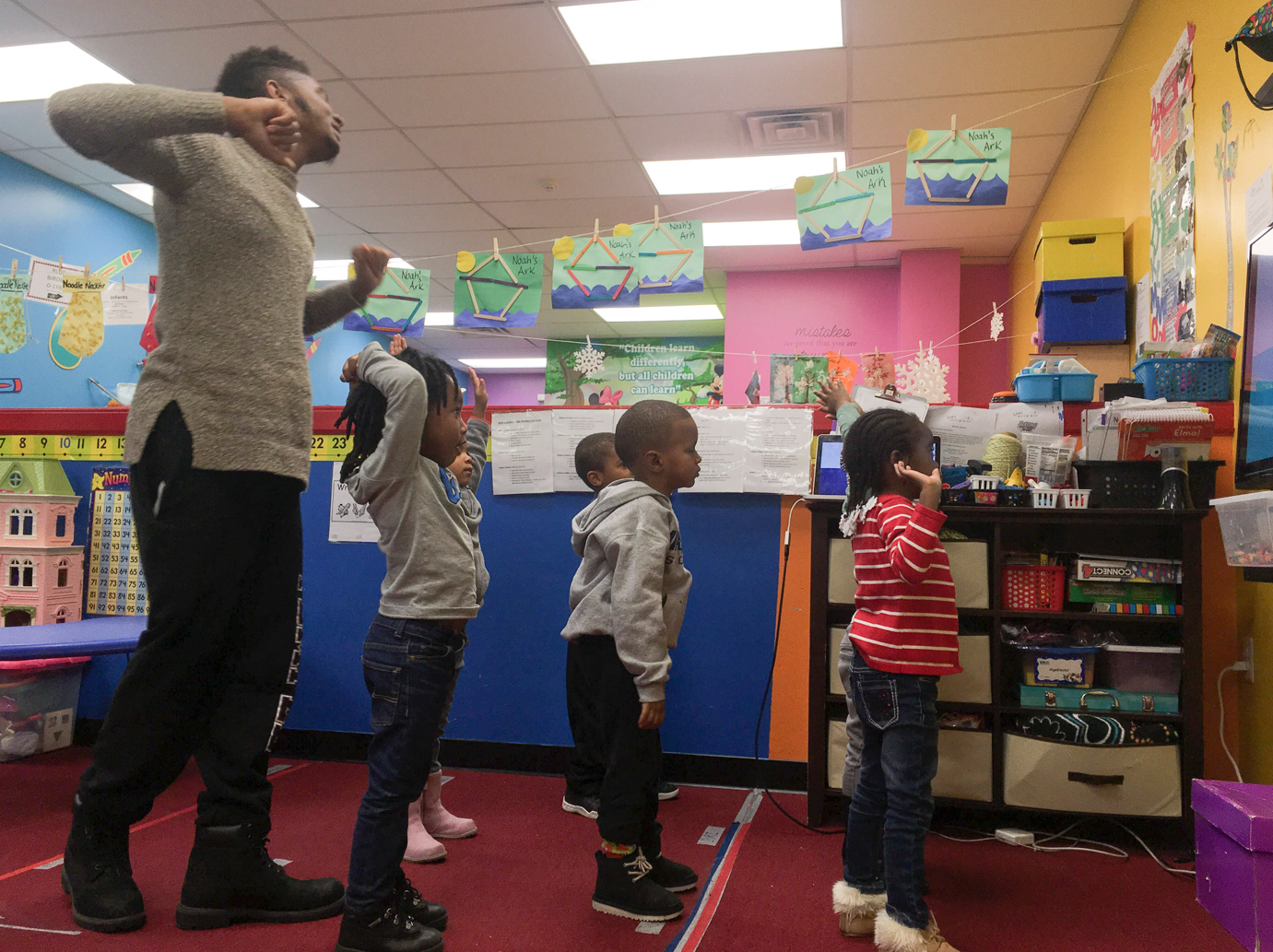

Bowman sends her children to Lisa’s Learning Center on Sedgley Avenue in Strawberry Mansion. Having qualified caregivers watching over her children gives her confidence in their future and allows her to work more shifts at her job and provide for her children.

Bowman attended preschool as a child and remembered the impact that it had on her.

“I’ve been in school since I’ve been 2 years old and 10 months,” she said. “I feel like that has increased my independence. I do notice a difference in independence with my siblings. I went to college and stayed on campus, my brother stayed home.”

Elected officials share Bowman’s belief that preschool is a priority.

In January 2017, Philadelphia City Hall enabled a tax on soda. For every ounce of each sugary beverage, a cent and a half would go toward funding preschools.

In 2016, on the verge of their upcoming vote on the then proposed tax, city government formed the Philadelphia Commission on Universal Pre-Kindergarten to map out a plan on how to make universal preschool a reality.

In the commission’s report that April, they estimated that in 2012, 150 to 250 children in Strawberry Mansion were at risk of at least two of the following factors that can be detrimental to the development of children – lead exposure, child maltreatment, homelessness, low birth weight, inadequate prenatal care, low maternal education and teen pregnancy.

The report found fewer than 100 open slots for children in high-quality preschools in Strawberry Mansion.

“I was astonished by the cost and lack of quality care within my immediate neighborhood in Strawberry Mansion,” said state representative Donna Bullock, who serves the 195th district of the Pennsylvania State House. Her district is made up of large sections of North and West Philadelphia, including Strawberry Mansion where Bowman lives.

Bullock sent her children to a facility far from her house.

As a state representative, Bullock has been a champion for universal preschool education. She has received honors from the Parent-Child Home Program and Pre-K for PA for her ability to work with both parties to provide better funding for preschools.

The commission recommended to prioritize neighborhoods that have the highest concentration poverty and children at-risk of poor academic outcomes, as well as neighborhoods lacking quality preschools.

In its report, the commission defines quality preschool as a school that is properly licensed, taught by qualified teachers, addresses learning and developmental needs, supports children’s transition into kindergarten and addresses socioeconomic disparities between students.

Bullock has been involved with preschools her entire life. Her mother was a home-based child care provider and her first job out of law school was representing providers like her mother and helping with legal work. When she became a representative she refused to allow early childhood institutions to remain neglected.

“My husband and I wanted to be assets of the neighborhoods we come from and bring back the resources we took from it as kids and young scholars and now adults,” she said.

The problem for Bullock and other policymakers is that not everybody sees preschool as a necessity. Some view it as a luxury while others believe it does not make a difference.

“Some folks think early education should come out of the parent’s pockets and surprisingly, some folks still think that mothers should stay at home to teach her children herself,” said Bullock.

However, in today’s economy it may not be realistic to expect one parent to stay at home while the other parent works, especially in the case of low-income families who are often not able to provide resources with only one source of income.

“Do you know how much it is for daycare?” asked Bowman. “About $230 a week. Thats a lot.”

The average cost of center-based daycare in the United States is about $11,666 per year. The average income for young adults in Strawberry Mansion is about $19,400 annually. This means that there is roughly $7,700 left over for other expenses aside from daycare itself.

A big problem for many parents sending children to preschool programs is the expense. Nationally, the annual cost of center-based infant care averaged more than 40 percent of the state median income for a single mother.

“If it wasn’t for the help that I get with government assistant funding with CCIS, I wouldn’t be able to afford to send my children to preschool,” Bowman said.

CCIS stands for Child Care Information Systems. It is a government program that subsidizes the cost of preschool to low-income families.

While preschool may be a hefty expense, research has shown that money invested into early childhood education comes back to save money in other aspects.

The commission found that for every dollar invested into preschools, the city saved $4 to $16 on special education, social services, and an increase in tax revenue. They also found that children from low-income families benefited the most from access to high quality preschools.

“We’re spending 30 to 80 thousand dollars a year for prison,” said Bullock. “We could’ve used that money 25 years ago to make sure that person has a good start in life from the beginning”

As a child, Bullock attended preschool and her mother took advantage of every free event that she could find.

“My mom made sure she took me or the other kids to any free event at the library or museums,” she said. “Because of this, I got a lot of exposure to learn about different things.”

For many families in low-income neighborhoods, the word free is a blessing.

Titus Moolathara works at the Widener branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia. Last fall, Moolathara took part in a weekly vocabulary-building initiative called Words at Play. The program was open to children five years old and and younger and strived to teach toddlers foundational reading skills through games, singing and reading out loud.

On a regular day, around 150 children visit Widener. Moolathara sees the first-hand effects the library’s programs have on children in the neighborhood.

“This place is a refuge for them,” Moolathara said. “The library not only provides a safe environment but our after-school team offers reading and math help and many students use this resource to complete their homework.”

Another free service in Strawberry Mansion is the local Police Athletic League Center. PAL is a national organization that offers children a variety of free activities to participate in after school. Activities include gymnastics, basketball, homework clubs, computer labs and more. The Strawberry Mansion center is the latest to open in Philadelphia.

“The Strawberry Mansion PAL center is a positive environment for kids to spend time,” said Police Officer Ricardo Hanton, who runs the center. “Kids don’t have to worry about crossing over into certain neighborhoods and getting into disputes. It is a safe place for kids to learn and have fun at and keeps them off the streets while their parents are at work.”

In a safe setting like the PAL, children have the freedom to be themselves and act like kids, something that seemingly not enough children in Strawberry Mansion are able to do.

“The most important thing is to develop kids socially and prepare them to interact and to be ready to learn” Bullock said. “Whether you can afford preschool education or not, we are aware that early childhood education makes a difference in lives. It is what’s best for our kids and what’s best for their futures.”

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/d/embed?mid=1zUbMidLFOpERKVQKFHPB7T5LM6Ib3jTJ&w=640&h=480]

The HighScope Perry Preschool Study from the 1960s randomized 123 low-income African American children into two groups – one group received a comprehensive preschool program and the other received no preschool education.

The study found that approximately 65 percent of children in the preschool program went on to graduate high school compared to the 45 percent who received no early childhood education. The study also found that 76 percent of children who had preschool education were employed by age 40, making $5,000 a year more than the 62 percent of children who received no preschool education.

Barbara Wasik, a professor in the College of Education at Temple University, believes the most important difference between students that have had access to pre-kindergarten education and those who have not is that preschoolers are able to self-regulate by the time they get to kindergarten.

“They have already had a full year of knowing what it is like to be in school,” said Wasik, whose research is mostly focused on early childhood education. “Often times, their language skills are better developed and they often have a better awareness of print because they have been exposed to books and have been exposed to a lot of opportunities that have allowed them to engage in materials that they will see in kindergarten.”

Wasik started her career training to be a developmental psychologist. A lot of her work has been done in cities – in addition to teaching at Temple, each week she commutes to do research to at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. While observing preschools, Wasik noticed how often children spend their time in the classroom and the role their teachers play.

“I realized that kids spend a lot of time in schools and that teachers really matter,” she said. “Parents matter too, but teachers really matter.”

Outside of teaching and researching, Wasik has worked with her colleagues to develop interventions to work with preschool teachers and train them to teach children how to develop vocabulary skills.

“Being able to engage kids in conversation and to be able to help develop vocabulary skills is crucial at that age,” Wasik said. “Kids spend a long time in the classroom. Having a qualified teacher plays a big role in their development.”

“My kids imitate teachers,” said Bowman. “They’ll take turns being different teachers. They’ll want me to teach them like they’re in the school.”

– Text, video and images by Matt Rego and Katie Bandish.

Be the first to comment